Embark on a journey to master the fundamentals of algorithms and data structures! This guide simplifies complex concepts, making them accessible and easy to understand. Imagine building with digital LEGOs; algorithms are the instructions, and data structures are the organizational systems that allow you to create anything from a simple program to a complex application.

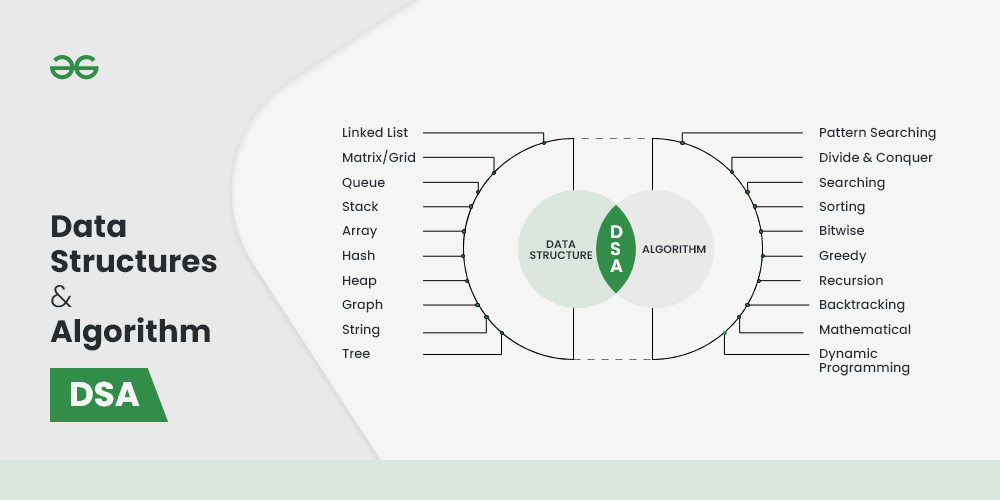

We’ll explore the essential building blocks of computer science, from the very definition of an algorithm to the practical applications of arrays, linked lists, stacks, queues, trees, and hash tables. You’ll learn how to measure efficiency, understand common algorithmic paradigms, and even build your own data structures using pseudocode. This knowledge will empower you to solve problems more efficiently and write better, more effective code.

Introduction to Algorithms and Data Structures

Algorithms and data structures are the fundamental building blocks of computer science. They are essential for creating efficient and effective software solutions. This section will introduce you to these concepts, explaining their roles and importance in the world of computing. Understanding these basics is crucial for any aspiring programmer or anyone seeking to solve computational problems effectively.

Fundamental Role of Algorithms in Computer Science

Algorithms are at the heart of every computer program. They provide a step-by-step procedure for solving a specific problem or performing a particular task. They are the instructions that a computer follows to transform input data into the desired output.Algorithms are critical because:

- They provide a systematic approach to problem-solving.

- They ensure that a task is performed consistently and reliably.

- They enable the automation of complex processes.

- They can be designed to optimize performance, minimizing resource usage like time and memory.

For example, consider the task of sorting a list of numbers. An algorithm like “Bubble Sort” provides a specific set of instructions to arrange the numbers in ascending order. Different sorting algorithms (e.g., Merge Sort, Quick Sort) exist, each with varying performance characteristics. The choice of algorithm depends on factors like the size of the data set and the desired performance.

Definition and Importance of Data Structures

Data structures are organized ways of storing and managing data in a computer’s memory. They determine how data elements are related to each other and how they can be accessed and modified. The choice of data structure significantly impacts the efficiency of algorithms that operate on the data.Data structures are important because:

- They provide efficient ways to store and retrieve data.

- They organize data in a way that makes it easier to process and manipulate.

- They enable the development of complex and efficient software systems.

- They optimize memory usage and improve the performance of algorithms.

Consider a phone book. The data structure used to store the names and phone numbers (like a hash table or a balanced tree) will dictate how quickly you can find a specific person’s number. A well-chosen data structure allows for fast lookups, insertions, and deletions, which is crucial for a responsive application.

Benefits of Understanding Algorithms and Data Structures for Problem-Solving

A solid understanding of algorithms and data structures equips you with powerful tools for tackling a wide range of problems. This knowledge enhances your ability to design efficient solutions, write optimized code, and solve complex computational challenges.The benefits include:

- Improved problem-solving skills: You can break down complex problems into smaller, manageable steps.

- Enhanced code efficiency: You can choose the right algorithms and data structures to optimize performance.

- Increased software scalability: Your solutions can handle larger datasets and more complex tasks.

- Better understanding of software design principles: You can create more robust and maintainable code.

For example, a programmer working on a social media platform would need to understand data structures like graphs (to represent relationships between users) and algorithms for searching (to find friends) and sorting (to display posts in a specific order). Without this knowledge, the platform would be slow and inefficient.

Common Areas Where Algorithms and Data Structures Are Used

Algorithms and data structures are fundamental to many areas of computer science and software development. Their application is widespread, from everyday applications to specialized scientific computations.Here are some common areas:

- Software Development: Algorithms are used in all software applications for tasks like sorting, searching, and data manipulation. Data structures organize the data used by the application.

- Database Management Systems (DBMS): DBMS use algorithms for indexing, querying, and transaction management. Data structures are used to store and retrieve data efficiently.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): AI and ML algorithms rely heavily on data structures for representing and processing data, and on specialized algorithms for training models and making predictions.

- Game Development: Game developers use algorithms for pathfinding, collision detection, and game physics. Data structures are used to manage game objects and their properties.

- Operating Systems: Operating systems use algorithms for process scheduling, memory management, and file system operations. Data structures organize the system’s resources.

- Networking: Network protocols and routing algorithms rely on data structures to manage network traffic and ensure efficient communication.

- Web Development: Web applications use algorithms for tasks like searching, sorting, and data processing on the server-side and client-side. Data structures are essential for organizing and displaying web content.

For instance, consider a search engine like Google. It utilizes sophisticated algorithms (e.g., PageRank) and data structures (e.g., inverted indexes) to efficiently search the web and return relevant results. The speed and accuracy of search results depend heavily on the underlying algorithms and data structures.

Core Concepts: Algorithms

Algorithms are the heart of computer science, providing the instructions computers follow to solve problems. Understanding algorithms is crucial for writing efficient and effective code. This section delves into the fundamental concepts of algorithms, covering their definition, efficiency, common paradigms, and different implementation approaches.

What an Algorithm Is

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure designed to solve a specific problem or accomplish a particular task. It’s a finite sequence of well-defined instructions that, when executed, will lead to a solution. These instructions are unambiguous and must be executable.Let’s illustrate this with a familiar example: making a sandwich.Here’s an algorithm for making a simple peanut butter and jelly sandwich:

- Get two slices of bread.

- Get peanut butter.

- Get jelly.

- Get a knife.

- Spread peanut butter on one slice of bread.

- Spread jelly on the other slice of bread.

- Put the two slices of bread together, peanut butter and jelly sides facing each other.

- Cut the sandwich in half (optional).

- Serve and enjoy!

This algorithm provides clear, concise instructions. Each step is a specific action, and following these steps in order will reliably produce a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Different algorithms can achieve the same result. For instance, you could spread the jelly first, or choose to cut the sandwich into triangles instead of halves.

Algorithm Efficiency and Big O Notation

Algorithm efficiency refers to how well an algorithm performs in terms of time and space (memory) usage. Analyzing efficiency is critical for choosing the best algorithm for a given task, especially when dealing with large datasets. We use Big O notation to describe the growth rate of an algorithm’s runtime or space requirements as the input size increases. It provides an upper bound on the algorithm’s complexity.Big O notation focuses on the dominant term in the function describing the algorithm’s runtime or space usage.

It provides a way to compare algorithms regardless of the specific hardware or programming language used.Here’s a breakdown:

- O(1)

-Constant Time: The algorithm takes the same amount of time regardless of the input size. Example: Accessing an element in an array by its index. - O(log n)

-Logarithmic Time: The runtime increases logarithmically with the input size. Example: Binary search in a sorted array. With each step, the search space is halved. - O(n)

-Linear Time: The runtime increases linearly with the input size. Example: Iterating through a list to find a specific element. - O(n log n)

-Linearithmic Time: Common in efficient sorting algorithms. Example: Merge sort and quicksort. - O(n2)

-Quadratic Time: The runtime increases proportionally to the square of the input size. Example: Nested loops, such as in some basic sorting algorithms (e.g., bubble sort). - O(2n)

-Exponential Time: The runtime doubles with each addition to the input size. Example: Solving the Traveling Salesperson Problem using a brute-force approach. - O(n!)

-Factorial Time: The runtime grows extremely quickly. Example: Finding all possible permutations of a set.

For instance, consider two algorithms to search for an element in a list:* Linear Search (O(n)): This algorithm checks each element one by one. If the list has 10 elements, it might take up to 10 steps. If the list has 100 elements, it might take up to 100 steps.

Binary Search (O(log n))

This algorithm works on sorted lists. It repeatedly divides the search interval in half. If the list has 16 elements, it takes at most 4 steps (log 2(16) = 4). If the list has 1024 elements, it takes at most 10 steps (log 2(1024) = 10).Binary search is significantly more efficient for large lists.

Common Algorithmic Paradigms

Algorithmic paradigms are general approaches or strategies for designing algorithms to solve problems. They provide a framework for thinking about and solving a wide variety of computational challenges.

- Divide and Conquer: This paradigm involves breaking down a problem into smaller subproblems, solving the subproblems recursively, and then combining their solutions to solve the original problem. Examples include merge sort, quicksort, and binary search. The core idea is to reduce a complex problem into manageable parts.

- Greedy Algorithms: These algorithms make the locally optimal choice at each step, hoping to find a global optimum. They work by selecting the best immediate option without considering the long-term consequences. Examples include the coin change problem (making change with the fewest coins) and Huffman coding (data compression). Greedy algorithms are often simpler to implement but don’t always guarantee the best solution.

- Dynamic Programming: This technique solves problems by breaking them down into overlapping subproblems and storing the solutions to these subproblems to avoid recomputation. It is often used for optimization problems. Examples include the Fibonacci sequence calculation, the knapsack problem, and shortest path problems (e.g., Dijkstra’s algorithm). Dynamic programming often involves creating a table to store intermediate results.

- Backtracking: This approach systematically searches for a solution by trying different possibilities and undoing choices that lead to dead ends. It’s often used for solving constraint satisfaction problems. Examples include solving Sudoku puzzles, the N-Queens problem, and finding paths in a maze.

Iterative vs. Recursive Approaches

Iterative and recursive approaches are two fundamental ways to implement algorithms. Understanding the differences between them is crucial for writing efficient and readable code.* Iterative Approach: This approach uses loops (e.g., `for` loops, `while` loops) to repeat a block of code until a condition is met. It’s generally more efficient in terms of memory usage because it doesn’t involve creating multiple function calls on the call stack.* Recursive Approach: This approach involves a function calling itself to solve a smaller version of the same problem.

Each recursive call adds a new frame to the call stack. While elegant for certain problems, excessive recursion can lead to stack overflow errors if the recursion depth is too large.Let’s illustrate this with the calculation of factorial (n!). The factorial of a non-negative integer n, denoted by n!, is the product of all positive integers less than or equal to n.

Iterative Factorial Calculation:“`pythondef factorial_iterative(n): result = 1 for i in range(1, n + 1): result – = i return result“`This iterative approach uses a `for` loop to multiply the numbers from 1 to n. Recursive Factorial Calculation:“`pythondef factorial_recursive(n): if n == 0: return 1 else: return n

factorial_recursive(n – 1)

“`This recursive approach defines the factorial in terms of itself. The base case is when n is 0, returning 1. Otherwise, it returns n multiplied by the factorial of n-1.While the recursive approach is often more concise and elegant for problems that naturally lend themselves to recursive definitions, the iterative approach is usually more efficient in terms of memory usage, particularly for large values ofn*.

The iterative approach avoids the overhead of function calls associated with recursion.

Core Concepts

Now that we’ve covered the basics of algorithms, let’s dive into the world of data structures. Understanding data structures is crucial for efficient data organization and manipulation, which directly impacts the performance of your algorithms. Think of data structures as the building blocks for storing and arranging data in a way that makes it easier to access, modify, and process.

Data Structures: Definition and Role

Data structures are fundamental organizational methods for storing and managing data in a computer. They define how data elements are related to each other and how they can be accessed and manipulated. Choosing the right data structure is critical for the efficiency of your programs.

The primary role of data structures is to:

- Organize data in a meaningful way.

- Facilitate efficient access to data elements.

- Enable efficient modification of data elements.

- Provide a framework for implementing algorithms.

Arrays vs. Linked Lists

Arrays and linked lists are two fundamental data structures used for storing collections of data. They differ significantly in how they store data and how data elements are accessed. Here’s a comparison:

| Feature | Array | Linked List |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Allocation | Contiguous memory allocation (all elements stored in adjacent memory locations). | Non-contiguous memory allocation (elements can be stored anywhere in memory). |

| Access Time | Constant time access (O(1))

|

Linear time access (O(n))

|

| Insertion/Deletion | Potentially slow (O(n))

|

Potentially fast (O(1))

|

| Size | Fixed size (size needs to be defined at the time of declaration). Some languages provide dynamic arrays. | Dynamic size (can grow or shrink as needed). |

| Memory Usage | Can be more memory-efficient if the size is known in advance. | Can have higher memory overhead due to storing pointers. |

Stacks and Queues: Properties and Uses

Stacks and queues are abstract data types (ADTs) that are used to store and manage data in a specific order. They are characterized by their access methods, which define how elements are added and removed.

Stacks follow the Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) principle. Imagine a stack of plates; the last plate you put on top is the first one you take off.

- Properties: Elements are added (pushed) and removed (popped) from the top.

- Uses: Function call management (call stack), expression evaluation, undo/redo functionality, and browser history.

Queues follow the First-In, First-Out (FIFO) principle. Think of a queue of people waiting in line; the first person in line is the first one served.

- Properties: Elements are added (enqueued) at the rear and removed (dequeued) from the front.

- Uses: Task scheduling, print queues, breadth-first search (BFS) in graph algorithms, and managing requests in a system.

Binary Search Tree Illustration

A binary search tree (BST) is a tree-based data structure where each node has at most two children, referred to as the left child and the right child. The value of each node in the left subtree is less than the value of the node, and the value of each node in the right subtree is greater than the value of the node.

This structure allows for efficient searching, insertion, and deletion of data.

Here’s a simple text-based illustration of a BST with the values 5, 2, 8, 1, 3, 7, and 9:

5

/ \

2 8

/ \ / \

1 3 7 9

In this example:

- 5 is the root node.

- 2 is less than 5, so it’s in the left subtree.

- 8 is greater than 5, so it’s in the right subtree.

- 1 and 3 are in the left subtree of 2.

- 7 and 9 are in the right subtree of 8.

This structure allows for a search algorithm that can efficiently locate a specific value by traversing the tree based on comparisons with the node values.

Common Data Structures: Arrays and Lists

Arrays and lists are fundamental data structures in computer science, providing organized ways to store and manipulate collections of data. Understanding their characteristics, differences, and performance implications is crucial for writing efficient and effective algorithms. This section explores arrays and linked lists, covering their core properties and practical applications.

Arrays

Arrays are contiguous blocks of memory used to store a fixed-size sequence of elements of the same data type.Arrays possess several key characteristics:* Accessing Elements: Elements in an array are accessed using an index, which represents their position in the sequence. Indexing typically starts at 0. For instance, in an array `arr` of size 5, `arr[0]` refers to the first element, `arr[1]` to the second, and so on.

This direct access capability makes retrieving an element’s value very fast.* Memory Allocation: Arrays allocate a contiguous block of memory when they are created. This means all elements are stored next to each other in memory. The size of the array is usually determined at the time of creation. This contiguous allocation allows for efficient access but also implies that the array’s size is often fixed, although dynamic arrays exist to address this limitation.

Arrays offer

O(1)* (constant time) access to any element given its index.

Linked Lists

Linked lists are linear data structures where elements are not stored in contiguous memory locations. Instead, each element, called a node, contains the data and a pointer (or link) to the next node in the sequence. Linked lists provide flexibility in terms of insertion and deletion compared to arrays, but they often sacrifice direct access efficiency.Different types of linked lists exist, each with unique properties:* Singly Linked List: Each node contains data and a pointer to the next node.

The list has a head (the first node) and a tail (the last node), where the tail’s next pointer is usually `NULL` (or `None`).* Doubly Linked List: Each node contains data and two pointers: one to the next node and one to the previous node. This allows for traversal in both directions (forward and backward).* Circular Linked List: The last node’s pointer points back to the head of the list, creating a circular structure.

This can be singly or doubly linked.

Performance Comparison: Arrays vs. Linked Lists

The choice between arrays and linked lists depends on the specific operations and their frequency in your application. Here’s a comparison of their performance characteristics:

| Operation | Array | Linked List |

|---|---|---|

| Accessing an element | O(1) | O(n) |

| Searching an element | O(n) | O(n) |

| Insertion at the beginning | O(n) | O(1) |

| Insertion at the end | O(1) (amortized) | O(n) |

| Deletion at the beginning | O(n) | O(1) |

| Deletion at the end | O(1) (amortized) | O(n) |

* Accessing an element: Arrays are significantly faster for accessing elements by index (O(1) vs. O(n)).* Insertion and Deletion: Linked lists excel at inserting and deleting elements at the beginning (O(1) vs. O(n) for arrays). Arrays may require shifting elements, which takes O(n) time. Insertion/Deletion at the end has varying performance depending on the array implementation (e.g., dynamic arrays with amortized O(1) for insertion, but O(n) in the worst case when resizing).* Search: Both arrays and linked lists have O(n) time complexity for searching, assuming the data is unsorted.

Sorted arrays allow for binary search (O(log n)).

Reversing a Linked List (Pseudocode)

Reversing a linked list is a common operation that involves changing the order of the nodes. The following pseudocode demonstrates an iterative approach to reverse a singly linked list:“`pseudocodefunction reverseLinkedList(head) prev = NULL current = head next = NULL while current != NULL next = current.next // Store the next node current.next = prev // Reverse the pointer prev = current // Move prev to current current = next // Move current to next return prev // New head of the reversed listend function“`This pseudocode reverses the pointers of each node, effectively changing the order of the list.

The `prev` pointer keeps track of the previously reversed node, `current` is the node being reversed, and `next` stores the following node before the current node’s pointer is changed. The algorithm iterates through the list, updating the pointers until the end of the list is reached.

Common Data Structures: Stacks and Queues

In the realm of data structures, stacks and queues are fundamental linear structures that organize data in specific ways. They are simple yet powerful tools for managing data flow and are used extensively in computer science. Understanding these structures is crucial for designing efficient algorithms and programs.

Stacks: The LIFO Principle

Stacks adhere to the Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) principle. Imagine a stack of plates; the last plate you put on top is the first one you take off. This order is fundamental to how stacks operate.A real-world example of a stack in action is the undo/redo functionality found in many software applications. When you perform an action (like typing text or drawing a shape), it’s “pushed” onto a stack.

The “undo” operation then “pops” the last action off the stack, effectively reversing it. Similarly, “redo” would push the undone action back onto the stack, re-executing it. This mechanism provides a history of actions, allowing users to easily revert or repeat changes.

Queues: The FIFO Principle

Queues, on the other hand, follow the First-In, First-Out (FIFO) principle. Think of a queue of people waiting in line at a bank. The first person in line is the first one served.A common real-world example of a queue is a printer queue. When you send multiple documents to a printer, they are placed in a queue. The printer processes the documents in the order they were received – the first document sent is the first one printed.

This ensures that all print jobs are handled in a fair and orderly manner.

Stack and Queue Applications in Programming

Stacks and queues are indispensable tools in programming. They are employed in various applications, contributing to the efficiency and organization of code.Here are some examples:

- Function Calls: When a function is called, its information (parameters, return address, local variables) is pushed onto a stack (the call stack). When the function finishes, its information is popped off the stack, and control returns to the calling function. This mechanism allows for nested function calls and proper program execution.

- Breadth-First Search (BFS): BFS, a graph traversal algorithm, uses a queue to explore nodes level by level. Nodes are added to the queue as they are discovered, and the algorithm processes nodes in the order they were added, ensuring all nodes at a given depth are visited before moving to the next depth.

- Expression Evaluation: Stacks are often used to evaluate mathematical expressions, especially those involving parentheses or operator precedence.

- Task Scheduling: Operating systems and other applications often use queues to manage tasks or processes, ensuring that tasks are executed in a fair and orderly manner.

Common Stack and Queue Operations

Both stacks and queues have a core set of operations that allow for adding, removing, and accessing elements. These operations are crucial for interacting with the data structures.Here’s a list of common stack and queue operations:

- Stack Operations:

- Push: Adds an element to the top of the stack.

- Pop: Removes the element from the top of the stack.

- Peek (or Top): Returns the top element without removing it.

- IsEmpty: Checks if the stack is empty.

- Queue Operations:

- Enqueue: Adds an element to the rear of the queue.

- Dequeue: Removes the element from the front of the queue.

- Peek (or Front): Returns the front element without removing it.

- IsEmpty: Checks if the queue is empty.

Common Data Structures

Data structures are fundamental to efficient algorithm design. They provide organized ways to store and manipulate data, enabling faster and more effective problem-solving. Choosing the right data structure is crucial for optimizing performance, especially when dealing with large datasets. We will explore one of the most versatile data structures: trees.

Common Data Structures: Trees

Trees are hierarchical data structures that mimic the structure of a tree in nature. They consist of nodes connected by edges. Each node can have zero or more child nodes, and each node has at most one parent node (except for the root node, which has no parent). Trees are used in a wide range of applications, including file systems, database indexing, and decision-making processes.

Binary Trees and Their Properties

Binary trees are a specific type of tree where each node has at most two children, referred to as the left child and the right child. This simple constraint leads to powerful properties and efficient operations.The core properties of binary trees are:

- Root Node: The topmost node in the tree, which has no parent.

- Nodes: Elements that store data and may have child nodes.

- Edges: Connections between nodes, representing relationships.

- Parent Node: A node that has one or more child nodes.

- Child Node: A node that is connected to a parent node.

- Leaf Node: A node with no children.

- Depth: The number of edges from the root to a specific node.

- Height: The maximum depth of any node in the tree.

Binary trees can be classified further into different types, such as complete binary trees, full binary trees, and balanced binary trees. The specific properties of each type influence the performance of operations like searching, insertion, and deletion. For example, a complete binary tree has all levels filled except possibly the last, which is filled from left to right. This property allows for efficient storage in an array.

Advantages of Using Binary Search Trees

Binary search trees (BSTs) are a special type of binary tree where the value of each node in the left subtree is less than the value of the node, and the value of each node in the right subtree is greater than the value of the node. This ordering allows for efficient searching, insertion, and deletion operations.The key advantages of using binary search trees are:

- Efficient Searching: The ordered structure allows for a binary search algorithm, resulting in logarithmic time complexity (O(log n)) for searching, insertion, and deletion in a balanced BST. This is significantly faster than linear search (O(n)) in an unsorted list, especially for large datasets.

- Ordered Data: The inherent ordering of the data allows for easy retrieval of minimum, maximum, and other ordered values.

- Dynamic Nature: BSTs can dynamically grow and shrink as data is added or removed, unlike static arrays.

- Implementation Simplicity: BSTs are relatively easy to implement compared to more complex data structures like hash tables.

However, it is important to note that the performance of a BST can degrade if the tree becomes unbalanced. In the worst-case scenario (e.g., a skewed tree where all nodes are on one side), the search time can become linear (O(n)). Techniques like self-balancing BSTs (e.g., AVL trees, Red-Black trees) are used to mitigate this issue by automatically rebalancing the tree during insertion and deletion operations, ensuring logarithmic time complexity.

Visual Representation of a Simple Binary Search Tree

Here’s a text-based representation of a simple binary search tree containing the numbers 5, 2, 8, 1, and 6:“` 5 / \ 2 8 / / 1 6“`In this tree:

- The root node is 5.

- The left child of 5 is 2, and the right child is 8.

- The left child of 2 is 1.

- The left child of 8 is 6.

- There are no other children.

The tree is structured such that the value of each node is greater than all values in its left subtree and less than all values in its right subtree. This organization allows for quick lookups. For example, to search for the value 6, we would start at the root (5), go right (because 6 > 5), and then go left from 8 (because 6 < 8), and we find the value. This illustrates the efficiency of the binary search tree structure.

Common Data Structures

Data structures are fundamental to computer science, providing organized ways to store and manage data.

Choosing the right data structure can significantly impact the efficiency of your algorithms. This section delves into one of the most powerful and versatile data structures: hash tables.

Common Data Structures: Hash Tables

Hash tables, also known as hash maps, are a widely used data structure that stores data in key-value pairs. They offer efficient performance for insertion, deletion, and search operations.The primary purpose of a hash table is to provide quick access to data based on a given key. This is achieved through a process called hashing, where the key is transformed into an index (or “hash”) within an array.

The value associated with the key is then stored at that index in the array.

How Hash Functions Work

Hash functions are the core component of hash tables. Their primary role is to convert a key of any data type (e.g., string, integer, object) into an integer index within the hash table’s underlying array.The ideal hash function should distribute keys evenly across the array, minimizing collisions. A good hash function should also be deterministic, meaning it always produces the same hash value for the same key.Here’s a breakdown of how hash functions typically operate:* Input: The hash function receives a key as input.

Processing

The key is processed using a specific algorithm. This could involve mathematical operations, bitwise manipulations, or a combination of both.

Output

The function produces an integer, which serves as the index for storing the key-value pair in the hash table.There are several common techniques used in hash functions:* Modulo Arithmetic: The most common approach involves using the modulo operator (`%`). The hash value is calculated as `key % array_size`. This ensures that the hash value falls within the bounds of the array.

Multiplication Method

This method involves multiplying the key by a constant (typically a fractional value between 0 and 1), extracting the fractional part of the result, and then multiplying it by the array size.

Polynomial Hash Functions

These functions treat the key as a polynomial and evaluate it using a prime number. They are particularly effective for strings.Example:Let’s consider a simple hash function using the modulo operator. Suppose we have an array of size 10, and our key is the integer

25. The hash function would calculate

25 % 10 = 5

The key-value pair would then be stored at index 5 of the array.

Strategies for Handling Collisions in Hash Tables

Collisions occur when two different keys produce the same hash value, leading to both keys trying to occupy the same index in the array. Handling collisions is crucial for maintaining the efficiency of hash tables. Several strategies are employed to resolve collisions:* Separate Chaining: This is a common technique where each index in the hash table array points to a linked list (or another data structure) that stores all the key-value pairs that hash to that index.

When a collision occurs, the new key-value pair is simply added to the linked list at that index. In this scenario, imagine an array of size 5. Key “apple” and key “banana” both hash to the same index (let’s say index 2). With separate chaining, index 2 would point to a linked list containing both (“apple”, value_of_apple) and (“banana”, value_of_banana).* Open Addressing: In open addressing, if a collision occurs, the algorithm probes for an empty slot in the array.

There are several probing techniques:

Linear Probing

The algorithm checks the next available slot in the array.

Quadratic Probing

The algorithm checks slots at increasing quadratic intervals.

Double Hashing

The algorithm uses a second hash function to determine the probing interval. For instance, using linear probing, if index 2 is occupied, the algorithm might check index 3, then index 4, and so on, until an empty slot is found.The choice of collision resolution strategy depends on factors like the expected load factor (the ratio of the number of elements to the size of the hash table) and the desired performance characteristics.

Time Complexity of Common Hash Table Operations

The time complexity of hash table operations is a key factor in their efficiency. However, the performance depends heavily on the collision resolution strategy and the quality of the hash function.Here’s a comparison of the time complexity of common hash table operations with those of arrays and linked lists:

| Operation | Array | Linked List | Hash Table |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insertion | O(1) or O(n) (if resizing) | O(1) | O(1) (average case), O(n) (worst case due to collisions) |

| Deletion | O(n) | O(n) | O(1) (average case), O(n) (worst case due to collisions) |

| Search | O(n) | O(n) | O(1) (average case), O(n) (worst case due to collisions) |

* O(1)

Constant Time

Operations take the same amount of time regardless of the number of elements. O(n)

Linear Time

Operations take time proportional to the number of elements.

In the average case, hash tables provide significantly faster performance for insertion, deletion, and search operations compared to arrays and linked lists. However, in the worst-case scenario (e.g., many collisions), the performance can degrade to O(n).

Sorting Algorithms

Sorting is a fundamental concept in computer science, and it involves arranging a collection of items, such as numbers or strings, into a specific order. This order is typically numerical or alphabetical, either ascending or descending. The importance of sorting cannot be overstated, as it underpins many other algorithms and data structures, enabling efficient searching, data analysis, and database management.

Think of organizing a library – finding a book would be incredibly difficult without the books being sorted by author or title. Similarly, sorting allows for the rapid retrieval of information within a dataset, optimizing the performance of various computational tasks.

The Concept of Sorting and Its Importance

Sorting algorithms arrange data elements based on a defined comparison criteria, placing them in a specific order. This order is crucial for efficient data processing. Without sorting, searching through a large dataset becomes a time-consuming linear process. The efficiency gained from sorting directly impacts the performance of numerous applications.The significance of sorting extends to:

- Search Optimization: Sorted data enables the use of efficient search algorithms like binary search, which significantly reduces the time required to find a specific element.

- Data Analysis: Sorting simplifies data analysis tasks by allowing for easy identification of minimum, maximum, median, and other statistical measures.

- Database Management: Databases rely heavily on sorting for indexing, query optimization, and data retrieval.

- Algorithm Design: Many other algorithms, such as graph algorithms and computational geometry algorithms, utilize sorting as a pre-processing step.

Bubble Sort

Bubble sort is one of the simplest sorting algorithms. It repeatedly steps through the list, compares adjacent elements, and swaps them if they are in the wrong order. The pass through the list is repeated until no swaps are needed, which indicates that the list is sorted.The process of Bubble Sort involves these steps:

- Comparison: Starting from the beginning of the list, compare each adjacent pair of elements.

- Swapping: If the elements are in the wrong order (e.g., the first element is greater than the second in an ascending sort), swap them.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 1 and 2 for each pair of adjacent elements, moving from the beginning to the end of the list. After each pass, the largest element “bubbles up” to its correct position at the end of the list.

- Repetition: Repeat the process until no swaps are made during a pass, indicating that the list is sorted.

Example: Let’s sort the array [5, 1, 4, 2, 8] using bubble sort:

- First Pass:

- (5, 1, 4, 2, 8) -> (1, 5, 4, 2, 8)

-Swap 5 and 1 - (1, 5, 4, 2, 8) -> (1, 4, 5, 2, 8)

-Swap 5 and 4 - (1, 4, 5, 2, 8) -> (1, 4, 2, 5, 8)

-Swap 5 and 2 - (1, 4, 2, 5, 8) -> (1, 4, 2, 5, 8)

-No swap, 8 is in correct position.

- (5, 1, 4, 2, 8) -> (1, 5, 4, 2, 8)

- Second Pass:

- (1, 4, 2, 5, 8) -> (1, 4, 2, 5, 8)

-No swap - (1, 4, 2, 5, 8) -> (1, 2, 4, 5, 8)

-Swap 4 and 2 - (1, 2, 4, 5, 8) -> (1, 2, 4, 5, 8)

-No swap - (1, 2, 4, 5, 8) -> (1, 2, 4, 5, 8)

-No swap

- (1, 4, 2, 5, 8) -> (1, 4, 2, 5, 8)

- Third Pass:

- (1, 2, 4, 5, 8) -> (1, 2, 4, 5, 8)

-No swap - (1, 2, 4, 5, 8) -> (1, 2, 4, 5, 8)

-No swap - (1, 2, 4, 5, 8) -> (1, 2, 4, 5, 8)

-No swap

- (1, 2, 4, 5, 8) -> (1, 2, 4, 5, 8)

The array is now sorted: [1, 2, 4, 5, 8].

Insertion Sort

Insertion sort builds a sorted array one element at a time. It iterates through the input list, taking one element at a time and inserting it into its correct position within the already sorted portion of the list.The steps involved in Insertion Sort are:

- Iteration: Start with the second element in the list (index 1).

- Comparison: Compare the current element with the elements before it in the sorted portion of the list.

- Shifting: If the current element is smaller than an element in the sorted portion, shift the larger elements one position to the right to make space for the current element.

- Insertion: Insert the current element into its correct position in the sorted portion.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 2-4 for all remaining elements in the list.

Complexity Analysis:

- Best-case time complexity: O(n)

-Occurs when the input array is already sorted. In this case, only one comparison is needed for each element. - Average-case time complexity: O(n 2)

-Occurs when the input array is randomly ordered. - Worst-case time complexity: O(n 2)

-Occurs when the input array is sorted in reverse order. - Space complexity: O(1)

-Insertion sort is an in-place sorting algorithm, meaning it sorts the array within the original memory space without requiring additional memory proportional to the input size.

Merge Sort

Merge sort is a divide-and-conquer sorting algorithm. It works by recursively dividing the unsorted list into smaller sublists until each sublist contains only one element (which is considered sorted). Then, it repeatedly merges the sublists to produce new sorted sublists until there is only one sorted list remaining.Advantages and Disadvantages of Merge Sort: Advantages:

- Efficiency: Merge sort has a time complexity of O(n log n) in all cases (best, average, and worst), making it very efficient for large datasets.

- Stability: Merge sort is a stable sorting algorithm, meaning that it preserves the relative order of equal elements in the sorted output.

- Parallelism: Merge sort is well-suited for parallel processing, as the subproblems can be solved independently and then merged.

Disadvantages:

- Space Complexity: Merge sort has a space complexity of O(n), as it requires additional memory to store the merged sublists. This can be a significant drawback for very large datasets.

- Overhead: The overhead of recursion and merging can make merge sort less efficient than simpler algorithms like insertion sort for small datasets.

Searching Algorithms

Searching algorithms are fundamental to computer science, enabling us to locate specific data within larger datasets. Efficient searching is crucial for applications ranging from database management and web search to everyday tasks like finding a contact in your phone. The choice of search algorithm depends heavily on the structure of the data and the frequency of searches.

The Concept of Searching within Data Structures

Searching involves the process of finding a specific element, or a collection of elements, within a data structure. The goal is to determine if the target element exists and, if so, to identify its location (e.g., index in an array, node in a linked list). The efficiency of a search algorithm is often measured by the number of comparisons or operations it needs to perform, directly impacting its execution time.

The choice of the most suitable search algorithm depends on factors such as the size of the dataset, the frequency of searches, and whether the data is sorted or unsorted.

Binary Search Algorithm and Its Requirements

Binary search is a highly efficient search algorithm used to find a specific element within a sorted array. It operates on the principle of repeatedly dividing the search interval in half.

- Requirements: Binary search has a strict requirement: the data must be sorted. This is because the algorithm relies on the sorted order to eliminate half of the search space with each comparison. If the data is not sorted, binary search will not work correctly.

- How it works:

- Start with the middle element of the array.

- Compare the middle element with the target value.

- If the target value matches the middle element, the search is successful.

- If the target value is less than the middle element, search the left half of the array.

- If the target value is greater than the middle element, search the right half of the array.

- Repeat steps 1-5 on the selected half until the target value is found or the search interval is empty (target not found).

- Time Complexity: Binary search has a time complexity of O(log n), where n is the number of elements in the array. This logarithmic time complexity makes it exceptionally efficient for large datasets. For example, searching for a name in a phone book with a million entries would, at most, take around 20 comparisons using binary search (log₂1,000,000 ≈ 20).

Linear Search Algorithm and Its Time Complexity

Linear search, also known as sequential search, is a straightforward search algorithm that iterates through a data structure, element by element, to find a target value. It does not require the data to be sorted, making it a simple option when dealing with unsorted datasets.

- Steps involved:

- Start at the beginning of the data structure.

- Compare the target value with the current element.

- If the target value matches the current element, the search is successful. Return the index.

- If the target value does not match, move to the next element.

- Repeat steps 2-4 until the target value is found or the end of the data structure is reached.

- If the end of the data structure is reached without finding the target value, the search is unsuccessful.

- Time Complexity: Linear search has a time complexity of O(n), where n is the number of elements in the data structure. In the worst-case scenario (target element is the last element or not present), the algorithm must examine every element. For instance, searching for a specific product in a small online store with 100 items might take, on average, 50 comparisons, but in a store with 10,000 items, the average would be 5,000 comparisons.

Comparison of Linear Search and Binary Search

Linear search and binary search are both fundamental search algorithms, but they differ significantly in their approach and efficiency. The choice between them depends on the specific characteristics of the data and the application’s performance requirements.

| Feature | Linear Search | Binary Search |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirement | Unsorted or Sorted | Sorted |

| Algorithm | Sequential search through the data structure. | Repeatedly divides the search interval in half. |

| Time Complexity (Best Case) | O(1) (target is the first element) | O(1) (target is the middle element) |

| Time Complexity (Average Case) | O(n/2) | O(log n) |

| Time Complexity (Worst Case) | O(n) | O(log n) |

| Space Complexity | O(1) | O(1) |

| Suitable for | Small datasets, unsorted data, infrequent searches. | Large datasets, sorted data, frequent searches. |

Binary search offers significantly better performance for sorted datasets, particularly as the size of the dataset increases. However, it requires the overhead of sorting the data initially if it’s not already sorted. Linear search is simpler to implement and can be used on unsorted data, but it is less efficient for larger datasets.

Algorithm Design Techniques

Understanding algorithm design techniques is crucial for efficiently solving computational problems. These techniques provide systematic approaches to develop effective and optimized algorithms. Mastering these techniques allows you to break down complex problems into smaller, manageable subproblems and devise solutions that are both elegant and performant.

Divide and Conquer Approach

The divide and conquer approach is a powerful algorithm design paradigm that involves recursively breaking down a problem into two or more smaller subproblems of the same or related type, until these become simple enough to be solved directly. The solutions to the subproblems are then combined to produce a solution to the original problem.The key steps in divide and conquer are:

- Divide: The original problem is divided into a number of subproblems.

- Conquer: The subproblems are solved recursively. If the subproblems are small enough, they are solved directly.

- Combine: The solutions to the subproblems are combined to obtain the solution to the original problem.

An illustrative example is the Merge Sort algorithm.

Merge Sort Example:

The Merge Sort algorithm sorts a list by repeatedly dividing the list into smaller sublists until each sublist contains only one element (which is inherently sorted). These sublists are then repeatedly merged to produce new sorted sublists until there is only one sorted list remaining.

Here’s how Merge Sort works:

- Divide: The list is divided into two halves.

- Conquer: Each half is sorted recursively using Merge Sort. This process continues until we have sublists of size 1.

- Combine: The sorted sublists are merged to produce a larger sorted list. This merging process continues until the entire list is sorted.

For example, to sort the list [38, 27, 43, 3, 9, 82, 10]:

- The list is divided into [38, 27, 43, 3] and [9, 82, 10].

- Each sublist is further divided and sorted recursively until we have sublists of size 1.

- The sublists are merged: [3, 27, 38, 43] and [9, 10, 82].

- Finally, the two sorted sublists are merged to produce the sorted list: [3, 9, 10, 27, 38, 43, 82].

Dynamic Programming and Its Uses

Dynamic programming is an algorithmic technique for solving optimization problems by breaking them down into simpler subproblems and solving each subproblem only once, storing the results in a table for later use. This approach avoids redundant computations and leads to significant efficiency gains, especially for problems with overlapping subproblems. Dynamic programming is particularly useful for problems where the optimal solution can be constructed from the optimal solutions of its subproblems.The core principles of dynamic programming include:

- Optimal Substructure: The optimal solution to a problem can be constructed from optimal solutions to its subproblems.

- Overlapping Subproblems: The problem can be broken down into subproblems that are reused multiple times.

Common uses of dynamic programming:

- Shortest Path Problems: Algorithms like Dijkstra’s algorithm and the Bellman-Ford algorithm use dynamic programming to find the shortest path between nodes in a graph.

- Knapsack Problem: This optimization problem, which involves selecting items to maximize value within a weight constraint, is efficiently solved using dynamic programming.

- Sequence Alignment: Algorithms for aligning biological sequences, such as the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm, utilize dynamic programming to find the optimal alignment.

- Fibonacci Sequence: Dynamic programming can significantly improve the efficiency of calculating Fibonacci numbers by storing and reusing previously computed values, avoiding redundant recursive calls.

Fibonacci Sequence Example:

Without dynamic programming, calculating the nth Fibonacci number involves repeated calculations of the same Fibonacci numbers.

Using dynamic programming, we can calculate Fibonacci numbers more efficiently.

- Define a Table: Create a table (array) to store the Fibonacci numbers.

- Base Cases: Initialize the first two values (F[0] = 0, F[1] = 1).

- Iterative Calculation: Calculate the remaining Fibonacci numbers iteratively, using the formula F[n] = F[n-1] + F[n-2], storing each result in the table.

- Result: The nth Fibonacci number is found in F[n].

This approach avoids redundant calculations, leading to an improved time complexity compared to a naive recursive implementation.

Greedy Algorithm Approach

The greedy algorithm is a straightforward approach to problem-solving that makes the best local choice at each step with the hope of finding a global optimum. This approach is often used for optimization problems, where the goal is to find the best possible solution among a set of possible solutions. It is called “greedy” because at each step, it chooses the option that appears to be the best at that moment, without considering the consequences of this choice in the future.The key characteristics of a greedy algorithm include:

- Optimal Substructure: The problem exhibits optimal substructure, meaning that an optimal solution to the problem can be constructed from optimal solutions to its subproblems.

- Greedy Choice Property: A globally optimal solution can be arrived at by making locally optimal choices (greedy choices).

Examples of problems suitable for the greedy approach include:

- Activity Selection Problem: Choosing the maximum number of non-overlapping activities from a set of activities with start and finish times.

- Fractional Knapsack Problem: Selecting items with fractional amounts to maximize value within a weight constraint.

- Huffman Coding: Constructing an optimal prefix code for data compression.

- Minimum Spanning Tree (MST): Finding the minimum-cost spanning tree in a weighted graph (e.g., Kruskal’s algorithm, Prim’s algorithm).

Fractional Knapsack Problem Example:

Suppose we have a knapsack with a maximum weight capacity of 50 kg and a set of items, each with a weight and a value. The goal is to maximize the total value of items placed in the knapsack without exceeding its capacity.

The greedy approach for the fractional knapsack problem is as follows:

- Calculate Value-to-Weight Ratio: For each item, calculate the value-to-weight ratio (value / weight).

- Sort Items: Sort the items in descending order based on their value-to-weight ratio.

- Select Items: Iteratively select items from the sorted list, starting with the item with the highest ratio, and add as much of each item as possible to the knapsack until the knapsack is full. If an item cannot be fully added, add a fraction of it to fill the remaining capacity.

For example, consider the following items:

- Item 1: Weight = 10 kg, Value = 60

- Item 2: Weight = 20 kg, Value = 100

- Item 3: Weight = 30 kg, Value = 120

1. Calculate Value-to-Weight Ratio:

- Item 1: 60/10 = 6

- Item 2: 100/20 = 5

- Item 3: 120/30 = 4

2. Sort Items:

Sort items based on the value-to-weight ratio in descending order: Item 1, Item 2, Item 3.

3. Select Items:

- Add Item 1 (10 kg, value = 60). Remaining capacity: 40 kg.

- Add Item 2 (20 kg, value = 100). Remaining capacity: 20 kg.

- Add a fraction of Item 3 (20 kg, value = 80). The knapsack is now full.

The total value in the knapsack is 60 + 100 + 80 = 240. This approach guarantees an optimal solution for the fractional knapsack problem.

Flowchart Illustrating the Steps of a Specific Algorithm Design Technique

The following flowchart illustrates the steps involved in the greedy algorithm approach, using the example of the fractional knapsack problem.

Flowchart Description:

The flowchart starts with the problem statement “Fractional Knapsack Problem” and then proceeds to the following steps:

- Start

- Input: Knapsack capacity, items (weight, value)

- Calculate Value-to-Weight Ratio: Calculate the value-to-weight ratio for each item (value / weight).

- Sort Items: Sort items in descending order based on the value-to-weight ratio.

- Capacity Remaining = Knapsack Capacity

- For each item in sorted order:

- If item.weight <= capacity remaining:

- Add item to knapsack.

- Capacity remaining = capacity remaining – item.weight

- Else:

- Add fraction of item to knapsack.

- Capacity remaining = 0

- End For

- Output: Total value in knapsack.

- End

The flowchart clearly Artikels the decision-making process within the greedy algorithm. It starts with input, calculation, and sorting, then iterates through the sorted items, deciding whether to add the whole item or a fraction of it based on the remaining capacity of the knapsack. The algorithm terminates when all items have been considered or the knapsack is full, and outputs the total value.

Last Point

In conclusion, this exploration of algorithms and data structures provides a solid foundation for any aspiring programmer or computer scientist. By understanding these core concepts, you’ll be well-equipped to tackle a wide range of challenges and develop innovative solutions. Remember, practice is key! Continue experimenting with these ideas and build your skills through hands-on projects. The world of computer science awaits!